Blockchain bridge security - Part 3

This is 3rd article of the Bridge security series. Check out Part 1 and Part 2

This article explains Arbitrary call execution with the help of two implementation specific examples:

- Attacker steals ether.

- Attacker tricks minting logic.

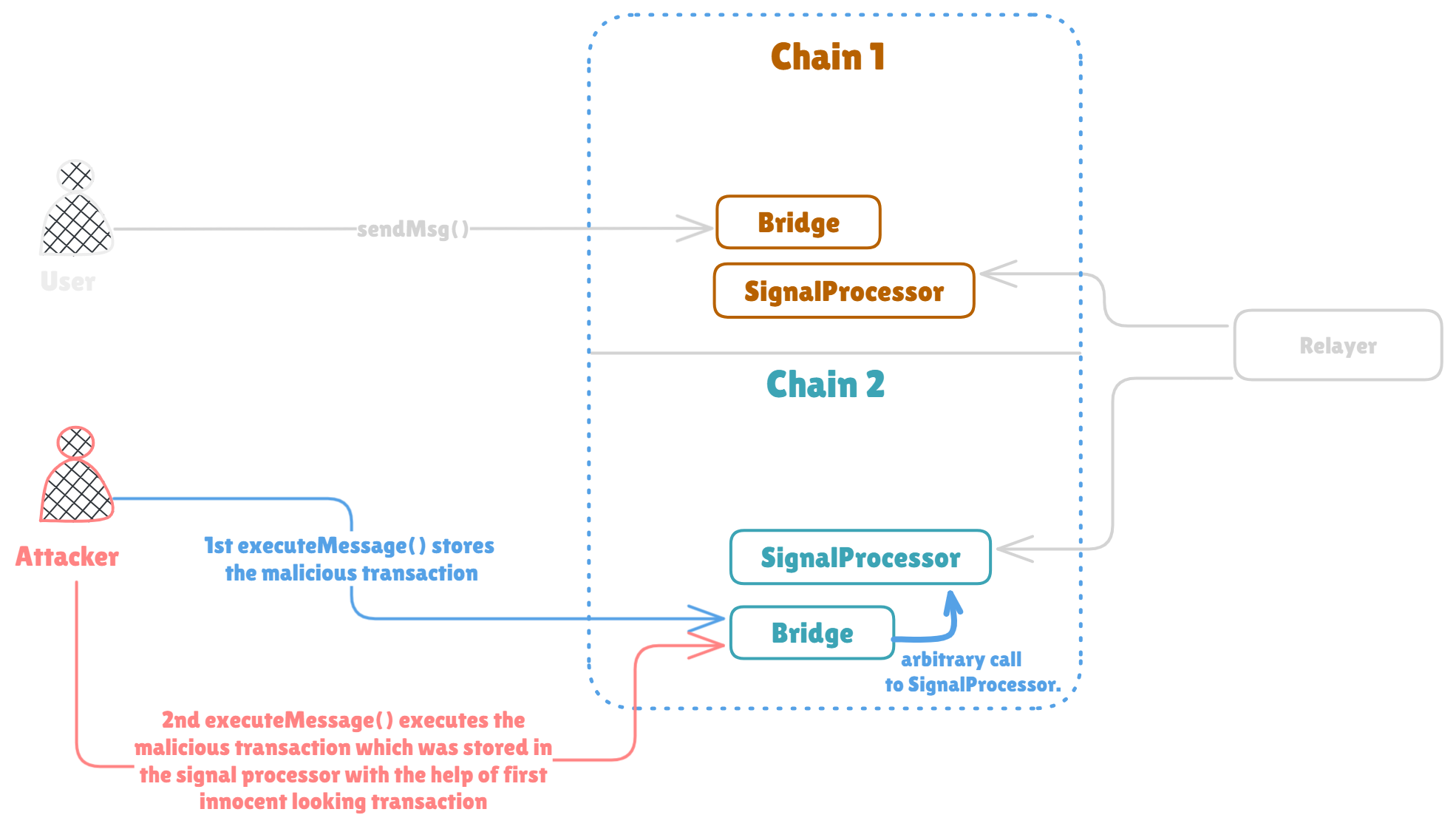

Arbitrary call execution

This vulnerability is possible because the bridge contract in this example allows arbitrarily calling any other contract.

There are two POCs for the explanation related to the current implementation. Both use nested messages:

Please refer the diagram as you read, for more visual understanding.

1. Attacker steals ether (test_sendMsg_nested())

Firstly it creates maliciousTransaction struct type variable, it's going to be a transaction to transfer 1 ether to the user address on destination chain.

It then creates a struct named transaction where it passes to address as a address of signalProcessor. The data would be the calldata for sendTx(bytes32) with the _msgHash argument passed as messageHash. The messageHash is hash of maliciousTransaction. see BridgeSignatureReplay.t.sol#L35-L36.

Then the test uses sendMsg() on BridgeSignatureReplay.t.sol#L50 to send the message across chain.

On BridgeSignatureReplay.t.sol#L56 destBridge.executeMessage() executes the transaction on the destination chain. This first call to executeMessage() executes the first transaction which will call the signal processor to store the malicious transaction hash. And it happens because in else{} on BridgeSignatureReplay.sol#L129 in executeMessage() executes. Because the if{} condition on BridgeSignatureReplay.sol#L120 fails as the transaction.to is signalProcessor address, the else{} executes. as can be seen on BridgeSignatureReplay.sol#L130 it executes the the malicious call i.e. the call to signalProcessor.sendTx() to store malicious data hash:(bool success,) = recipient.call{value: amount}(transaction.data);

Finally, On BridgeSignatureReplay.t.sol#L59, the test executes another destBridge.executeMessage(). This time the attacker actually passes the maliciousTransaction as an argument for destBridge.executeMessage(). On BridgeSignatureReplay.sol#L117 it's able to verify the message. Why ? because the attacker stored the malicious message with the first destBridge.executeMessage() call with innocent looking transaction on the BridgeSignatureReplay.t.sol#L56.

What happens in this second destBridge.executeMessage() call is, the if{} on the BridgeSignatureReplay.sol#L120 fails because the transaction.to is not address(0) or address(this), So the else{} executes, where it will perform a call() on recipient address (which is user address). And this is where the contract transfers the value as amount which is actually a transaction.value of 1 ether stated in maliciousTransaction struct.

And this is how the attacker gets 1 ether on the the destination chain without even sending it from the source chain in the first place .

2. Attacker tricks minting logic (test_sendMsg_nested_transfer())

It shows similar vulnerability as shown in test_sendMsg_nested() but here attacker tries to mint tokens on destination chain without burning his tokens on source chain.

Similar to previous test it starts with creating maliciousTransaction, where the to is address(0) and the data is calldata for mint(address,uint256). It also has innocent looking transaction named transaction, which assigns to as signalProcessor and data is the calldata for sendTx(bytes32) with the _msgHash argument passed as messageHash. The messageHash is the hash of maliciousTransaction.

Similar to the previous test it first executes the bridge.sendMsg() to send the message across chain.

If you see sendMsg() function. On BridgeSignatureReplay.sol#L61 it burns the valueToTransfer from transaction.from (in this case it's maliciousTransaction.from) if transaction.to is equal to address(0) or address(this) And if transaction.data is not equal to this.transfer.selector. While executing the bridge.sendMsg() in test on BridgeSignatureReplay.t.sol#L93, the transaction.to is signalProcessor, so if{} on BridgeSignatureReplay.sol#L56 never executes. So no tokens were burned on the source chain from the transaction.from (i.e. msg.sender or say attacker).

Then it executes the destBridge.executeMessage() with innocent looking transaction struct as an argument. as explained in the example above, it will call the signal processor to store the malicious transaction hash.

Finally it calls the destBridge.executeMessage() again with the maliciousTransaction. Since the maliciousTransaction struct has to field as address(0), the if{} on the BridgeSignatureReplay.sol#L120 will be executed. Then, since the maliciousTransaction.data is calldata for mint() and not for the transfer(), the if{} on the BridgeSignatureReplay.sol#L121 will fail and else{} on BridgeSignatureReplay.sol#L124 mints the decoded value (9999 ether) to the transaction.from (which in this case is maliciousTransaction.from. Alice's address).

The question is from where these 9999e18 ERC20 tokens came. The answer is from nowhere. because the user never burned his tokens on the source chain while executing sendMsg() function as discussed above.

In both the BridgeSignatureReplay.test_sendMsg_nested() and BridgeSignatureReplay.test_sendMsg_nested_transfer() the vulnerability is possible because the logic does not protect the bridge contract from anyone performing arbitrary calls to other address using the bridge itself. In this example that arbitrary address was signalProcessor.

To avoid this, generally a good idea is to limit the calls only to the trusted addresses and even while allowing calls to the trusted address it's important to check if it's prone to any vulnerability (As it was in this case). Also, depending on the logic it's good idea to not have a function that can be used to make calls to arbitrary address.

Next part (Part 4) shows:

- Chain id spoofing

- Hash collision

- Lack of signature expiry check